Nothing much to say about this good and detailed breeding report. You can use it as a reference for breeding other Dorcus species as well. Interestingly, there seem to be two types of Dorcus alcides, a short mandible one with a massive body and a slimmer type with elongated mandibles.

Introduction

These pages present the breeding/rearing of Dorcus alcides. Discussion on the breeding/rearing follows natural history of the insect, which is thought useful for breeding/rearing.

Dorcus alcides is considered as the world’s tenth longest and the widest living stag beetles. 102.3 mm may be the recorded maximum length of a wild-caught male imago. That means, for beetle breeding/rearing enthusiasts, that the male of this subspecies has a potential of growing up to 102.3 mm long or even longer. The following discussion first introduces its natural history and then emphasizes its breeding/rearing methods to win good results.

2. Natural history

2.1 Description: Male 33.0-102.3 mm including mandibles; Female 38.5-48 mm. Wide, somewhat flat. Dull black with blackish anntenae and legs.

2.2 Habitat: Tropical rain forests.

2.3 Range: Confined to Sumatra Is., Indonesia.

2.4 Food: Imago saps tree juice and larva feeds rotten hardwood tree.

2.5 Life cycle: The insect life cycle is said to be largely unknown in a natural setting. Under captive rearing (26 degrees C. in summer; 18 degrees C. in winter) of one generation, however, the author has experienced the following:

Upon the transfer of larvae singly into rearing bottles filled with substrate

1. Duration of larva:

Male: about 10-12 months (L1: 1 month; L2: 1 month; and L3: 8-10 months); and

Female: 6 months (L1: 1 month; L2: 1 month; and L3: 4 months)

2. alias of pupa: 1 month

Note that the duration of egg is about 1 month.

3. Breeding/rearing

3.1 Getting started

To begin with, what you need are:

1) A pair of imagoes (or several larvae);

2) Containers for breeding/rearing;

3) Food for imagoes;

4) Substrate for breeding; and

5) Decaying wood logs (length: about 15 cm; diameter: about 10 cm)

1) If you live in a country where this beetle is sold, please obtain a pair of imagoes (or several larvae). In choosing which individuals to buy, the following criteria are useful:

a) Wild-caught individuals:

Make sure: – When were they collected?: Avoid older individuals.

– Are they healthy-looking?: Check if there is no scar, injury

or missing part.

b) Captive reared individuals:

Make sure: – When did they emerge?: Avoid individuals of 8 months or older.

– Are they healthy-looking?: Check if there is no scar, injury

or missing part.

* Note that these two criteria are for imagoes. For choosing larvae, you can skip steps: – When

were they collected? and – When did they emerge?

2) Oviposition (egg-laying) requires some space; e.g. a container with a capacity of at least 5-6 liters (a lid is a must to stop the beetles from escaping). Get one and fill it with substrate (Also, see 4. A substrate for rearing Lucanid beetles).

– Put substrate into the container up to 5 cm high from the bottom, and press it hard by hand or any other means. Next, place one or two decaying wood logs on the top. Then, another layer of substrate should be added softly up to the point where the log(s) is/are almost covered. Female dugs a hole into the log and lays eggs in it.

– Then, let a mated female alone into the container. A male is vicious and may hurt a female in a stressful environment. A hand pairing would be good for mating. Feed them regularly (for food, see 3)).

– Keep temperature at 20-26 degrees C. and moisten the substrate and log to the extent which they are slightly wet.

3) For maintaining imagoes, you need to feed them with a pealed banana. It is better to place its pieces or slices on a small tray instead of applying them directly on the substrate, which causes them spoiling faster or prompts an occurrence of fruit flies or ticks. A pealed apple or a peach also serves as a suitable food.

4) See 4. A substrate for rearing Lucanid beetles. A substitute can be gardening black dirt. But it serves for a breeding purpose only, not for rearing by any means.

5) Find a fallen decaying wood in your area. A hardwood tree only. Preferably, Fagus sp. or Quercus sp. Cut it into pieces of about 15 cm in length. Then, keep them under fresh water for a day. This moistens the log and kills beetle’s predator organisms in it.

3.2 Rearing larvae

After a couple of months, take the female out of the container*. Then, carefully break down the log(s) to see if larvae have already hatched inside. If so, transfer them singly into plastic/glass bottles of an about 800 cc capacity, which is filled with substrate (see 4. A substrate for rearing Lucanid beetles). When you stuff substrate into empty bottles, the substrate should be pressed hard. When the substrate in the first bottles is almost eaten up, you need to transfer them singly into the second bottles. For males, you need to transfer them to a larger bottle (e.g. 1,500 cc with at least 15 cm diameter). Repeat this process, if need be.

* If you wish to obtain more eggs, let the female into another breeding container.

Repeat this process if you want.

When changing substrates, it is safer to stuff unused (new) substrate first from the bottom of the bottle, and then used one. The capacity ratio of the new to the used is 2-to-1. By so doing, beetle’s symbiotic bacteria, if any, would grow steadily in the substrate and enhance an ideal feeding environment for better larval growth (H. Kojima).From the author’s rearing, the duration of larvae are: Male: 10-12 months; and Female: 6 months.

3.3 Larva sexing

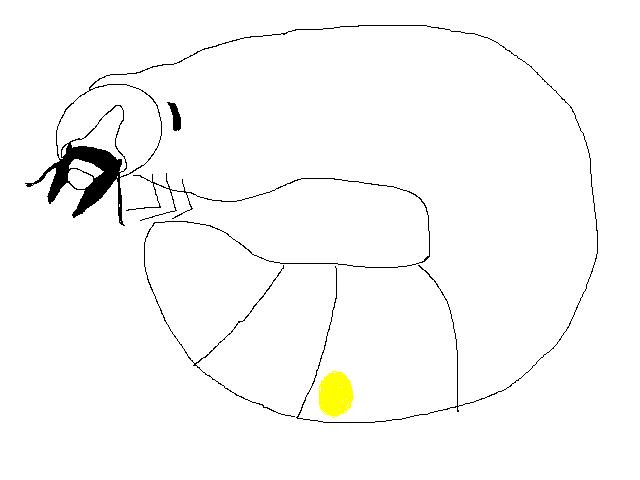

For sexing, see the following picture, Figure 3.3.

Figure 3.3 Yellowish ovaries may be visible underneath the 7-8th abdominal segment of the dorsal side of female larva after its mid L2 stage. No ovaries in male larva, as a matter of course. Besides, an L3 male reaches to 40-50 grams in weight when it is fully grown. Whereas the female remains up to 15 grams.

3.4 Maintaining pupae

After larvae turn noticeably yellowish in colour, stop changing substrates. Some time soon, the larvae undergo pupation. Often times, you see pupae through the (transparent) bottle wall against which their pupal cells are made. The best advice I give you at this point is patience: wait until one month after their emergence, and then take them out carefully. Newly emerged imagoes need 4 months for maturity. The life span of the imago is a few to several years after its emergence. Finally, there are some comments on the rearing. Many breeders/rearers have reported that, for this species, it is extremely difficult to attain male imagoes of Large Mandible Type under captive rearing even though the larvae are fully grown. They have reported that most of the captive reared male larvae become Small Mandible Types although their body size is large. And yet the mechanism as to what determines male’s mandible type has been unknown. My best advice for attaining Large Mandible Types is to rear as many larvae as possible. That would increase a chance to attain Large Mandible Types. The author has succeeded in rearing a Large Mandible Type at his first trial (see Figure 5.3). For this individual, the author used a 3 liter bottle for rearing and stuffed substrate softly into the bottle. To attain a larger male with large mandibles, the keys might be: to use a larger bottle; and to stuff the substrate softly into the bottle.

3.5 Breeding

Repeat the process: 3.1 Getting started.

4. A substrate for rearing Lucanid beetles

If you live in a place where you can get enough natural food for the species that you want to breed/rear, please skip this chapter. The natural food would be the best choice.

If not, on this page, I will tell you a recipe of a substrate for rearing Lucanid beetle larvae, which was originated by H. Kojima, a Japan’s leading expert on the breeding/rearing of Lucanid/Dynastine beetles.

To begin with, what you need are:

1) Decaying wood mulch (preferably Fagus sp. or Quercus sp.; no coniferous trees);

2) Wheat flour;

3) Natural water (avoid tap water, if possible); and

4) Active dry yeast (2 teaspoons / 5 liters of mulch)

* Capacity ratio of each, 1), 2) and 3), respectively: 10 to 1 to 1 (unit: liter)

The capacity ratio varies among the users of this substrate.

Procedures:

STEP 1: Make mulch completely dry under direct sun or by any other means.

STEP 2: Mix the mulch with wheat flour. Then, pour water into them and stir them well.

STEP 3: Put some yeast and stir well.

STEP 4: Keep it at 25 or more degrees C. This makes the substrate well fermented.

STEP 5: Stir it at least once a day until its temperature returns normal. It may take one month.

* Wheat flour is nutrition and also acts as an agent to prompt fermentation which is

beneficial to larvae. And when fermentation begins, the substrate temperature rises.

To make wood into mulch, some hobbyists use a home juicer/mixer. Please be aware that you must make the right choice of wood. This is important. If you are unsure of it, you can ask someone who knows it.

5. Acknowledgement

My special thanks are indebted to the following organizations and individuals: ‘The Beetle Ring’ (http://www.naturalworlds.org/beetlering/beetle_sites.htm) by Cameron Campbell, Administrator of ‘The Natural Worlds’ (http://www.naturalworlds.org/); ‘The Kanagawa Stag Beetle Club,’ a local chapter of Japan’s largest beetle hobbyist club, ‘The Stag Beetle Fools’ (http://www.mars.dti.ne.jp/~k-sugano/bakamono_web/index2e.html), and its members including Hiroshi Kojima; Benjamin Harink for sharing this wonderful hobby together and allowing me to contribute this article to his great beetle website; my father who has inspired me to pursue this interest; and my mother who has been patient enough for this unusual hobby of mine.

Contact:

I can be reached at http://www.geocities.com/kaytheguru/. Please feel free to visit my beetle website.

PS The following pictures are a male and a female Dorcus alcides imago captive reared by the author.

Leave a Reply